- GainGoat Fitness

- Posts

- Can Sound Influence Fat Gain and Muscle Adaptation?

Can Sound Influence Fat Gain and Muscle Adaptation?

A New Study Says it Can...

Training isn’t just about lifting weights, it’s about how your cells react to force. Every rep, stretch, and contraction sends mechanical signals that shape how muscle grows and how fat is stored. But mechanical stress isn’t limited to load or tension. Cells respond to a wide range of physical forces, and a recent study suggests one of the most unexpected inputs, sound, may influence cell behavior in ways no one predicted.

This matters because it pushes us to think beyond the familiar inputs of training and nutrition. It highlights the idea that your body is constantly reading the physical environment, and even subtle forces can shift how cells behave. The study at the center of this newsletter examined whether controlled sound waves could alter the development of fat cells and activate early stress-sensing pathways in muscle-related cells, a concept that challenges how we think about adaptation itself.

The Study at a Glance

Researchers used a direct acoustic stimulation system to expose two main cell types — developing fat cells and muscle-derived cells — to specific sound frequencies. The sound waves were delivered at approximately 100 Pa, which sits within the range of mechanical pressures that tissues can naturally experience. The key question was simple: Would cells treat sound as a meaningful physical force?

Figure 1a from the study: Visual of the sound emission system

Key Experimental Details

Frequencies tested: 440 Hz (low audible), 14 kHz (high audible), plus white noise

Duration: 2 hours and 24 hours

Measurements: gene expression, cell structure, adhesion area, lipid accumulation

Major Findings

Developing fat cells reacted strongly to sound.

Two master regulators of fat-cell formation dropped sharply:

Cebpa: reduced to ~0.18× baseline

Pparg: reduced to ~0.26× baseline

This led to fewer cells transitioning into fully developed fat-storing cells.

Fat accumulation decreased.

Total lipid content dropped by 13–15%, reflecting a meaningful impact on how these cells stored fat.

More cells remained in a “non-fat” state.

The proportion of undifferentiated cells increased by ~40%, meaning fewer cells committed to becoming fat cells.

Muscle-related cells activated early load-sensing signals.

Cells expanded their adhesion area by 15–20%, similar to how they react to physical tension.

A key stress-detection protein increased activity: phosphorylation of FAK (focal adhesion kinase).

These changes are upstream steps in how muscle cells interpret mechanical stress, but not indicators of hypertrophy.

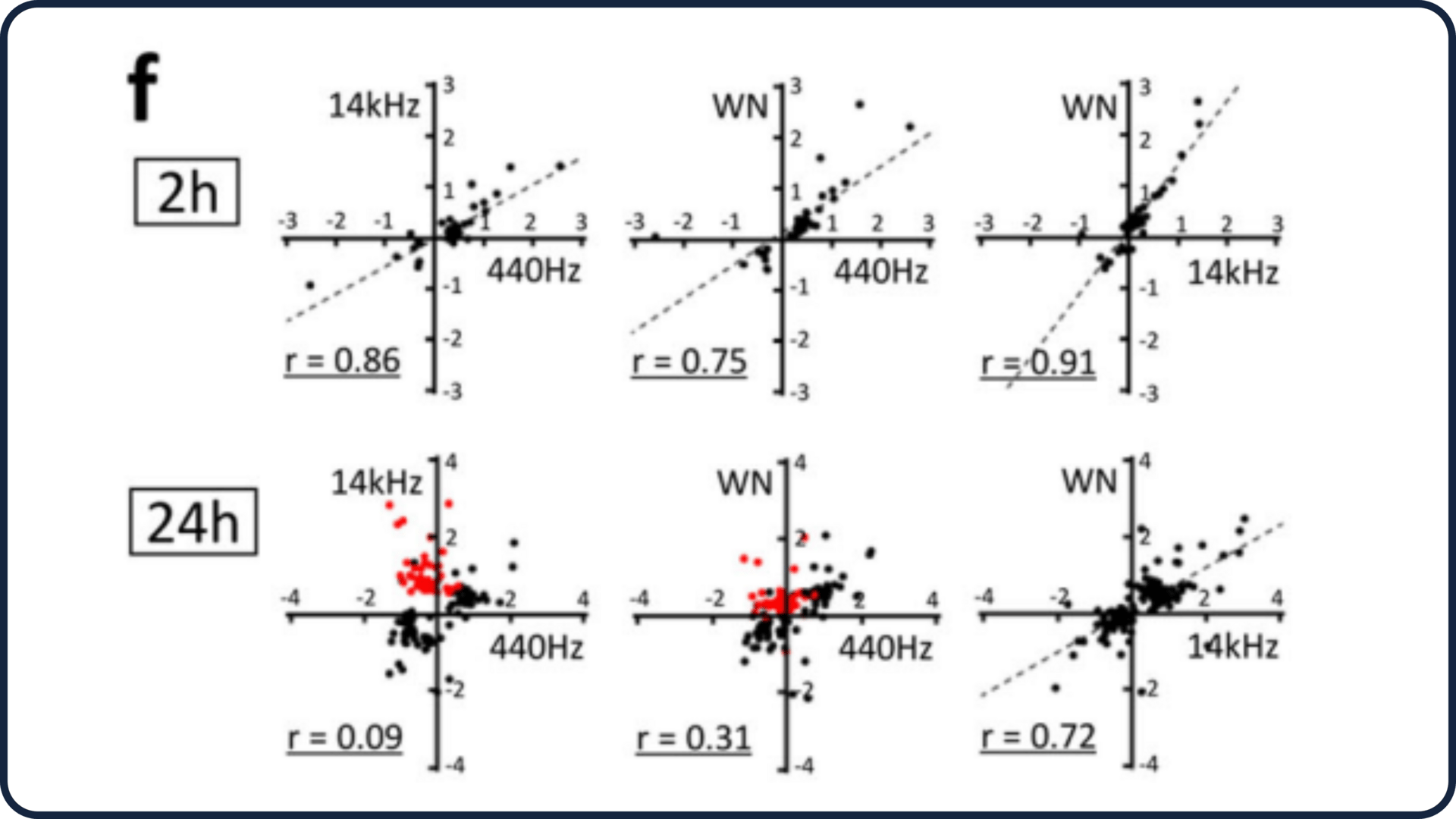

Different frequencies produced different long-term effects.

Early reactions were similar across frequencies.

After 24 hours, gene-response profiles diverged, suggesting that frequency-specific mechanical behaviors matter.

Overall, the evidence shows that cells do treat sound as a mechanical input, and fat and muscle-related cells interpret that input very differently.

Mechanisms and Physiology

How Cells Sense Sound as a Physical Force

Sound waves aren’t just noise, they’re tiny pulses of pressure. At the cellular level, even subtle pressure changes can deform membranes, shift proteins, or alter tension within the cell. Cells respond to these micro-forces through mechanosensors, systems designed to detect changes in their physical environment.

This study shows that cells treat controlled acoustic waves as a legitimate mechanical stimulus, triggering measurable changes in their internal signaling.

Why Fat-Forming Cells Reacted So Strongly

Developing fat cells are especially sensitive to physical cues because their “decision point”, whether to become a fat-storing cell or remain undifferentiated, depends heavily on environmental feedback. When exposed to specific sound waves, these cells dialed down the genes that normally push them toward fat storage.

Cebpa and Pparg aren’t minor markers, they are the master switches for fat-cell maturation. Suppressing them shifts the cell’s fate, explaining the large increase in cells that never became fat-storing cells. This isn’t fat burning, it’s altering the likelihood that certain cells become fat in the first place.

Muscle adaptation starts with mechanosensing. Cells detect tension, load, and deformation long before protein synthesis or hypertrophy occurs. One of the earliest steps is the activation of FAK, a protein that responds when the cell’s structure experiences force.

Sound waves triggered this same early signaling:

Increased FAK activity

Expanded adhesion areas

Cytoskeletal remodeling

These changes don’t imply muscle growth, but they do indicate that the cells recognized sound as a physical stressor. It demonstrates how sensitive the mechanosensing machinery is, it responds not only to weights and stretching but also to tiny oscillating pressures.

Frequency Matters: Why Different Frequencies Triggered Different Outcomes

While early reactions were similar across 440 Hz and 14 kHz, longer-term responses diverged. This likely comes down to how different frequencies physically move the fluid environment around the cells.

Lower frequencies generate more displacement and subtle fluid motion.

Higher frequencies create smaller displacements and more localized pressure changes.

Cells detected these differences, producing different gene-expression profiles over 24 hours. This reinforces the idea that mechanosensing is highly sensitive to the quality of the force, not just its magnitude.

Figure 1f from the study: Correlation scatter highlighting divergent gene effects

The PGE2 Signaling Layer

One of the most interesting findings was the involvement of PGE2 — a signaling molecule tied to inflammation, tissue remodeling, and metabolic regulation. When acoustic stimulation increased Ptgs2 expression, downstream PGE2 release increased as well.

This pathway is known to influence:

Fat-cell development

Cellular stress adaptation

Tissue repair responses

In fat cells, higher PGE2 tends to suppress differentiation. In muscle-related contexts, it plays a role in coordinating early-phase adaptation signals. The study confirms that blocking the PGE2 receptor canceled many of the sound-induced effects, showing its central role.

Figure 4a from the study: A simplified schematic of the signaling pathway

Practical Application For Lifters

This study shouldn’t be interpreted as a fat-loss method or a muscle-building tool. The experiments were done in controlled cell environments, not humans. But the physiological principles matter.

Here’s what lifters can take away:

Cells respond to far more types of physical input than just lifting weights.

Mechanosensing is incredibly sensitive.Fat-cell development is influenced by mechanical context.

The physical environment changes the likelihood that cells mature into fat-storing tissue.Muscle adaptation starts long before hypertrophy.

Early signals like FAK activation and cytoskeletal changes shape how muscles interpret training stress.Different forces create different signals.

Frequency, duration, and pressure all change how cells respond — similar to how tempo, load, and rep style matter in the gym.

The deeper message: your body is always reading its physical environment, and adaptation begins at the cellular level.

The Bottom Line

This study expands our understanding of how flexible and sensitive our biology really is. Sound waves, a force most people never think about, triggered measurable changes in pathways tied to fat formation and early muscle adaptation.

While this doesn't translate into a training strategy, it highlights a powerful truth:

mechanical signals shape the way tissues develop, adapt, and respond long before we see physical changes.

Understanding these signals gives lifters a deeper appreciation of why tension, load, and consistency matter so much for long-term progress.

Reference

Kumeta, M. et al. “Acoustic modulation of mechanosensitive genes and adipocyte differentiation.” Communications Biology

DOI: 10.1038/s42003-025-07969-1